To begin a discussion on the digital revolution in the humanities, we have asked some questions to our scientific advisors. Their answers will be published in eight issues between now and mid-October. Here, as fourth issue, Lutz Klinkhammer and Matteo Melchiorre.

Index

I) Agnese Accattoli and Davide Bondì.

II) Peter Burke and Elisabetta Benigni.

III) Marco Filoni and Erminia Irace.

VII

Lutz Klinkhammer

What generation do you feel you belong to?

To a “second” generation, one that has experienced a period of accelerated transformation, especially in the interweaving of private and professional life, followed by a digital transformation that was already underway previously, but less visible.

How and when did – in your personal experience – the digital revolution take place?

For me in the 80s with the use of the Personal Computer (Apple C) and the printer, but also as the protagonist of a humanistic project of basic research based on UNIX systems of the computer center to be activated with punch cards and very slow remote terminals but with excellent universal software.

Is the “old” way of working still present in your life? (for example: do you write by hand? do you use paper archives that you keep in order? do you usually read in the library?)

Yes, I still live in my hybrid world between paper(s) and computer and I struggle to make corrections to PDF texts in electronic form.

What do you think about the “digital” organization of scientific and cultural work? To what extent would you define the current way of working as new?

The current pandemic has given and will give even more impetus to the previously unthinkable digital reorganization of scientific work. If until now digital meant email, electronic sending of texts, mobile phones, sites, platforms and databases, now I see a new phase of more shared work, of videoconferences, podcasts and video presentations, of specific apps, of digital textmining, of libraries more digital than ever before. But the archive will remain largely paper-based, both for the amount of documentation and for the low marketability of the funds stored there.

Lutz Klinkhammer, contemporary historian of the Deutsches Historisches Institut in Rome, studies the history of the Italian and German totalitarian regimes, with a great attention to the history of studies and reflections on the policies of memory. He carries out an influential cultural mediation, in the historical field, between Germany and Italy.

VIII

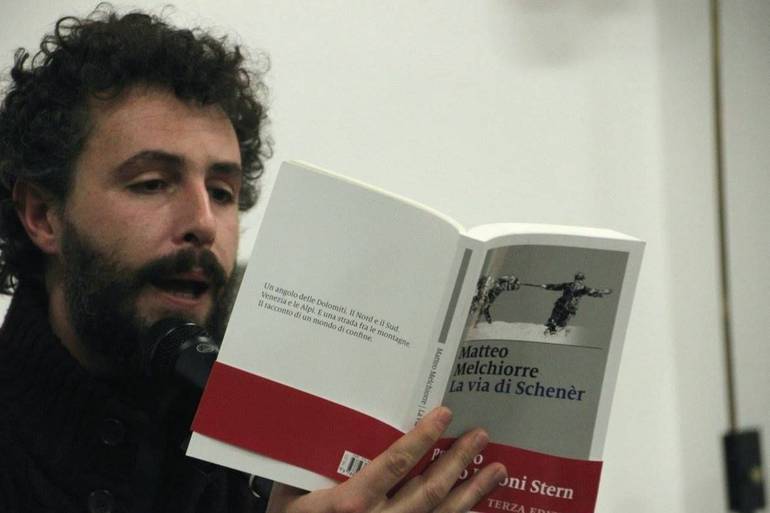

Matteo Melchiorre

What generation do you feel you belong to?

I belong to the generation that came after the 20th century. Years ago (in 2011) the TQ generation (i.e. Thirty-Quaranta) was identified in the literature, around which there was a lot of fuss about the strength or uselessness of this category; proof, if necessary, of the difficulty of reducing my so-called generation to some effective typologisation. Although I doubt the possibility of ascribing my generation to a strong generational belonging, and believing that in any case this very reticence to ascribe can be an identity feature far from secondary, I have the impression of belonging to an in-between generation, i.e. unfinished, not entirely in the “old” system and not entirely in the “new” system.

How and when did – in your personal experience – the digital revolution take place?

In my personal experience the digital revolution took place in four moments, the first one was playful, the second one was related to writing practice, the third one to the exercise of photography and the fourth one to research methods. The playful moment refers to the introduction at home (1991) of a computer to which I turned to as a new game option, with the game (the videogame was said to be in 1991) that joined my other playful devices. The second moment related to writing practice, that is when I was instructed to use (1992) a rudimentary word processing software. The third moment of my digital revolution, late if you like (2002), consisted in the purchase of a digital camera to replace the analogue one, a circumstance that changed my way of looking and remembering places, objects and time. The fourth moment, goes without saying, the so-called “advent of the web”, with the consequent remodulations of some research practices (bibliographic, archival, iconographic, etc.).

Is the “old” way of working still present in your life? (for example: do you write by hand? do you use paper archives that you keep in order? do you usually read in the library?)

Absolutely, yes. I continue to write by hand (especially in the “design” phases). In some cases I use paper cards instead of databases. I use to archive, in folders, notes and the like. As director of a Library, a Historical Archive and a Museum, it goes without saying that I live, one can say, between the Library, the Archive and the Museum, professions in which, today, the confrontation with the “new” way of working and with digital resources is the theme of programming, reflection and daily confrontation.

What do you think about the “digital” organization of scientific and cultural work? To what extent would you define the current way of working as new?

I believe more in the individual temperaments and intelligences that animate the instrumentation than in the instrumentation itself used in scientific-cultural work. I therefore think that the “digital” organization of cultural work is a mere qualifiable option in various directions and, for this reason, that it is not a guarantee of results that are neither blindly and by definition better nor structurally and nostalgically worse. A change of instruments can certainly support a change of method, but not determine it a priori.

Matteo Melchiorre, medievalist historian, director of the Library, Historical Archive and Museum of Castelfranco Veneto, studies and narrates, in a passionate and militant way, economic and social history from the Late Middle Ages onwards.