To begin a discussion on the digital revolution in the humanities, we have asked some questions to our scientific advisors. Their answers will be published in eight issues between now and mid-October. Here, as the fifth issue, Donald Sassoon and Luca Peretti.

Index

I) Agnese Accattoli and Davide Bondì.

II) Peter Burke and Elisabetta Benigni.

III) Marco Filoni and Erminia Irace.

IV) Lutz Klinkhammer and Matteo Melchiorre

IX

Donald Sassoon

What generation do you feel you belong to?

The post-war generation. The one the British call the baby boomers. In the West, the most fortunate generation in history.

How and when did – in your personal experience – the digital revolution take place?

It started more than thirty years ago when we had emails at university in London (which were not yet at the BBC World Service!).

Is the “old” way of working still present in your life? (for example: do you write by hand? do you use paper archives that you keep in order? do you usually go to the library to read?)

I’ve been writing on the computer for at least thirty-five years. I write almost nothing by hand. I have no paper archives. All my notes and notes are digital. Of course I go (I went before the current pandemic) to the library because most of the documents and books I need are not online.

What do you think about the “digital” organization of scientific and cultural work? To what extent would you define the current way of working as new?

An enormous progress without which today the situation would be even worse.

Donald Sassoon, Emeritus Professor at Queen Mary University, London. Starting from the study of political history, especially of the left, produces impressive work on both European cultural history and economic history from a comparative and global perspective. He carries out an influential cultural mediation between Great Britain and Italy. “Culture is the original world wide web”, he wrote in the conclusion of The culture of the Europeans (2006), where the digital revolution is brilliantly described.

X

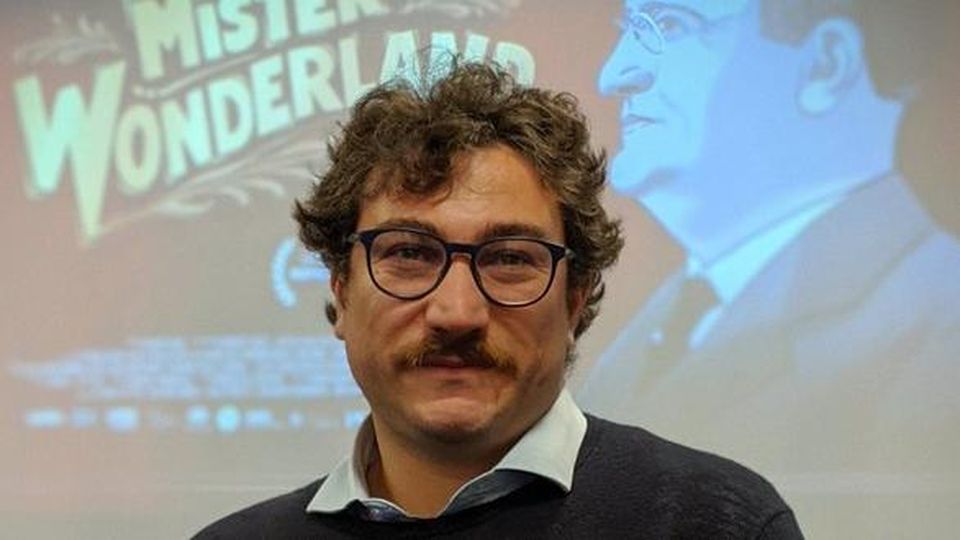

Luca Peretti

What generation do you feel you belong to?

I was born in the mid-eighties, I’d still say millenials (according to today’s categories), but there’s definitely a big leap between me and those who were born in the early nineties – that is, they tended to grow up with computers at home or at school, they were too small for Genoa and September 11, the twentieth century is really just a memory. I grew up with many places and ways still similar to those of my parents’ generation.

How and when did – in your personal experience – the digital revolution happen?

At the beginning of the 2000s, with the arrival of the internet at home, the first mobile phone, and a very timid computerisation even at school.

Is the “old” way of working still present in your life? (for example: do you write by hand? do you use paper archives that you keep in order? do you usually read in the library?)

Of course I do! I still take a lot of notes by hand, let’s say I make the two dimensions interact, for the more impromptu things (notes from films or books or in the archive) I write in general in pen, and then at most I copy on the computer things that I want to somehow keep or above all that I can easily find. But I use notebooks (which I keep quite out of order) and print practically all the papers I read. I go to the library very often, and even my office has a lot of paper, books but also notes, printed things etc.. When I set up a job, class to teach book article etc., I usually start from a concept map on a large sheet of paper.

What do you think about the “digital” organization of scientific and cultural work? To what extent would you define the current way of working as new?

I am very interested in the organization of “digital” work, every era seems to me to present us with new technologies to work with (printing, typewriter, etc.) and ours has perhaps accelerated the changes. Maybe, however, speed is the least interesting aspect, it’s more interesting to put these changes in a long term perspective, trying to grasp the fundamental points. After all, we have been dealing with digital tools for decades now. I don’t think there is in fact a new way of working, in the singular and in opposition to an old one both somehow homogeneous, but rather many different ways resulting from multiple approaches. I think we should avoid the risk of missing long lasting developments, insisting on creating new and old ones (so maybe we should create those monsters, according to the famous Gramscian quotation) instead of trying to understand media developments in a wider perspective. A possible research could then deal with defining first of all what we mean by digital and when it starts; then try to make lists of what really makes these tools new; finally, identify some moments of transition and some important technological inventions (including those that were abandoned) and understand how new and revolutionary the contemporaries felt about them.

Luca Peretti works in a frontier area between Italian cultural history, visual communication and film studies.